The following is a guest post by Aletha Maybank, MD, MPH, Deputy Commissioner, NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and Founding Director of the Center for Health Equity; Roger A. Mitchell, Jr., MD, Chief Medical Examiner, Washington, DC; and Javier Lopez, Assistant Commissioner, NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and Director of the Bureau of Systems Partnerships, Center for Health Equity.

"Addressing violence as a health issue is a paradigm shift that is critical not to winning an ideological battle, but ensuring that people are safe, that their children can thrive."

– Dr. Mary T. Bassett, Commissioner, New York City Health Department

Young people from many corners of our nation have cried out for years that their communities are dying too early as a result from gun violence and dying a slow death from the trauma it leaves. Now we are witness to young people from Helena, Montana to Parkland, Florida, and the Bronx in New York City leveraging their common agendas and calling for an end to partisan divide. But there is still something noticeably missing from advocacy for gun violence prevention today—pushing for a public health approach to stop violence from happening in the first place.

The World Health Organization defines health as “a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” In public health, we protect health for whole communities and populations. We look for patterns of disease, help shift people away from behaviors connected to disease, and address context to prevent risky behaviors in the first place. Whenever we have halted epidemics, we have used powerful public health methods.

However, since the 1990s the criminal justice system and law enforcement have been the primary architects of gun violence prevention efforts. A criminal justice focused prevention strategy has led to heavy emphasis on deterrence and punishment, especially for people of color.As we have learned from the opioid epidemic, preventing gun violence requires responses from beyond solely the criminal justice system and pinning communities as “bad people” in “bad places.”

So what is meant when we say gun violence is a public health issue?

- Gun violence is a behavior that can spread like an infection, leading to more violence. It contributes to avoidable injury, life lost, and impacts the mental health of entire communities, not only individuals. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there were 38,658 firearm related deaths in the United States in 2016; two-thirds of which are suicides, less than two percent are mass shootings.

- Gun violence is a symptom of the larger structural and historical contexts of our nation. Structural violence is created by racist policies and worsened by racial violence. These are headwinds created by our nation’s legacy of white supremacy, removal from land, slavery, Jim Crow, redlining, mass incarceration, and gentrification, to name a few. These policies have led to systems and institutions that perpetuate injustices, often invisible, based on race, gender, and income, and inflict physical, mental, and emotional harm on people and communities.

- Gun violence tears apart families and communities and often occurs at the crossroads of other forms of violence, such as intimate partner violence, child abuse, bullying, and other assaults on people. Trauma from violence can be passed down through generations putting children at an increased risk of chronic illnesses later in life, such as heart disease.

- Gun violence more often affects those pushed to the margins of society, causing big differences between groups in their experience and burden of gun violence, injury and early death. In addition to the many school students who have lost their lives within school walls over decades, people of color, cis and trans gendered women, LGBTQ identified people, people with mental illness, indigenous people, immigrants, and people with limited resources have predominantly carried the weight of gun violence. Today, Black men are six percent of the population but make up greater than 50 percent of all firearm related deaths.

Why is advocacy needed to push the health frame?

In 2015, Former U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher wrote in the Kelly Report, “Public health is the collective effort of a society to create the conditions in which people can be healthy; relative to violence, the public health approach has never been fully implemented.” The CDC, our lead public health agency, historically provides frameworks and evidence to guide state and local governments to tackle some of greatest public health crises issues, including obesity, smoking, HIV, motor vehicle collisions, and now opioid overdose prevention.

In 1979, the first Healthy People Surgeon General’s Report identified stress and violent behavior as one of 15 priority areas for public health action. During the 1980s and early 90s, much progress was made by the CDC and communities across the country in better understanding and preventing violence.

Then in the early 1990s, evidence showed that guns in the home increased the risk of homicide and suicide. Driven by a powerful gun lobby led by the National Rifle Association, an amendment by a Congressman from Arizona banned gun violence research connected to advocacy and, subsequently, funding for research was cut from the CDC’s budget by Congress. Now 20 years later, public health practitioners and scientists have not been able to move forward in fully addressing gun violence as a health issue since then.

Not only did this halt the CDC’s ability to study gun violence as a public health issue, it also inhibited the CDC’s ability to provide any level of comprehensive plan or guidance to local governments on data collection and evidence-based interventions; similar to how the CDC has done for obesity, smoking, and HIV.

There is a void and it needs to be filled. We must not play oppression Olympics or partisan politics with gun violence. We need more people, political will, policies, systems, and resources focused on preventing the root causes of gun violence through a public health lens for all types of gun related deaths — homicides, suicides, police-related, and mass shootings. This will allow us to:

- Have more useful data by setting up more collection and surveillance systems. Data will help us look at the health of whole populations, define why violence happens, analyze contributing factors (from structural to proximal), consider the influence of family and social networks in various regions across the country, prioritize which factors we can do something about, develop interventions, and study the effectiveness of these interventions (whether policy, research, or programs).

- Develop and implement policies that advance health justice, support health approaches to gun violence prevention, and dismantle the policies that perpetuate structural violence and worsen inequities.

- Protect our hospitals, schools, and other institutions by strengthening our ability and capacity to evaluate, respond to, and set up emergency preparedness and response systems.

- Deal with stress and trauma associated with gun violence by integrating trauma-informed practice, behavioral and mental health methods that respond to immediate and long-term needs, toxic stress and promote healing associated with trauma.

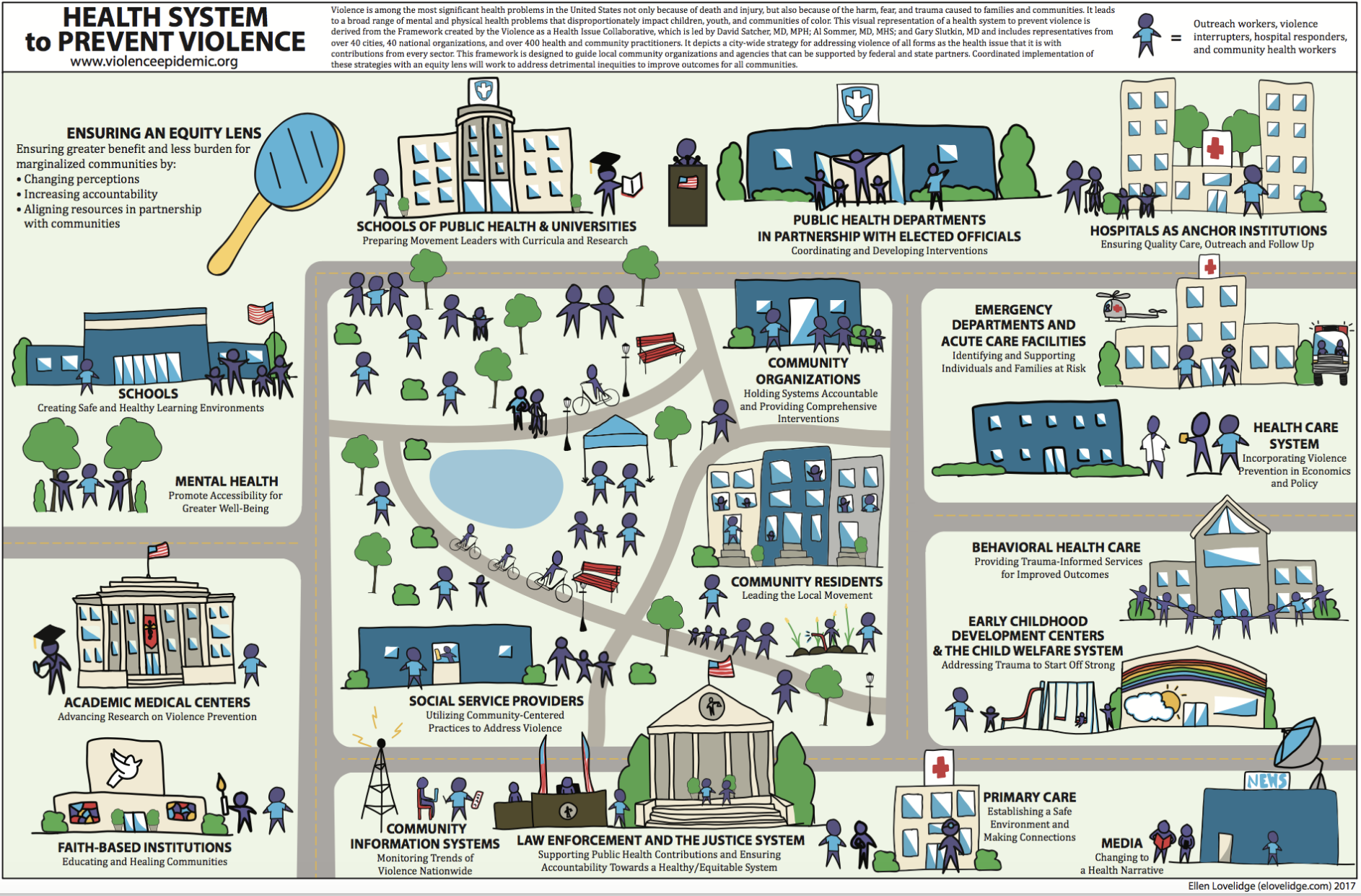

- Work across sectors to develop partnerships and alliancesandbe inclusive ofthose impacted the most by gun violence in developing interventions. We must engage community residents, community-based and faith-based organizations, coalitions, academia, and media in plans to see violence not as an inevitable consequence of modern life, but as a problem that can be understood and changed.

View our COVID-19 Safety Protocols for attending NYAM public events.